The Private Club in a Public Park

How a handful of elite law schools dominate the federal judiciary

Being a judge is a hard job. Aside from having to maintain an immense amount of knowledge on laws across a broad spectrum of sectors, you are always going to disappoint one side of a case. The Supreme Court, while deciding countless boring, technical cases hardly anyone in the general public reads, casts the final vote on some highly contentious issues, making ripples in the cultural and political spheres for generations after they leave the bench.

The gravity of the third, co-equal branch of government is immense, yet unlike the other two branches, there is not a lot of recourse if you have a bunch of judges ruling in ways you don’t like. This isn’t a piece about how responsive judges are to the population or proposing policy solutions like term limits or electing judges—something I think is the wrong solution—but a piece addressing how regular American lawyers are filtered out of serving in an entire branch of government. This will probably be a multi-part series, but for now, I want to anchor on how an extremely, extremely small group of law schools almost exclusively feed and influence the federal judiciary through appointments and clerkships.

Why does any of this matter, and why is it on Pioneering Oversight? Well, simply put, judges write law. Last week’s Antitrust Roundup shows just how much power judges have, and while I think there is immense value in having judges insulated from election cycles, it would still be nice to know where all these influential people hail from.1

The Private Club

The last time a justice attended a public law school was Justice Hugo Black, who attended the Alabama School of Law. He was appointed in 1937 and died in 1971.

The last Supreme Court Justice to have read for the law was Justice Robert Jackson, on the bench from 1941-54.

Today, eight of nine Supreme Court Justices went to Harvard or Yale.

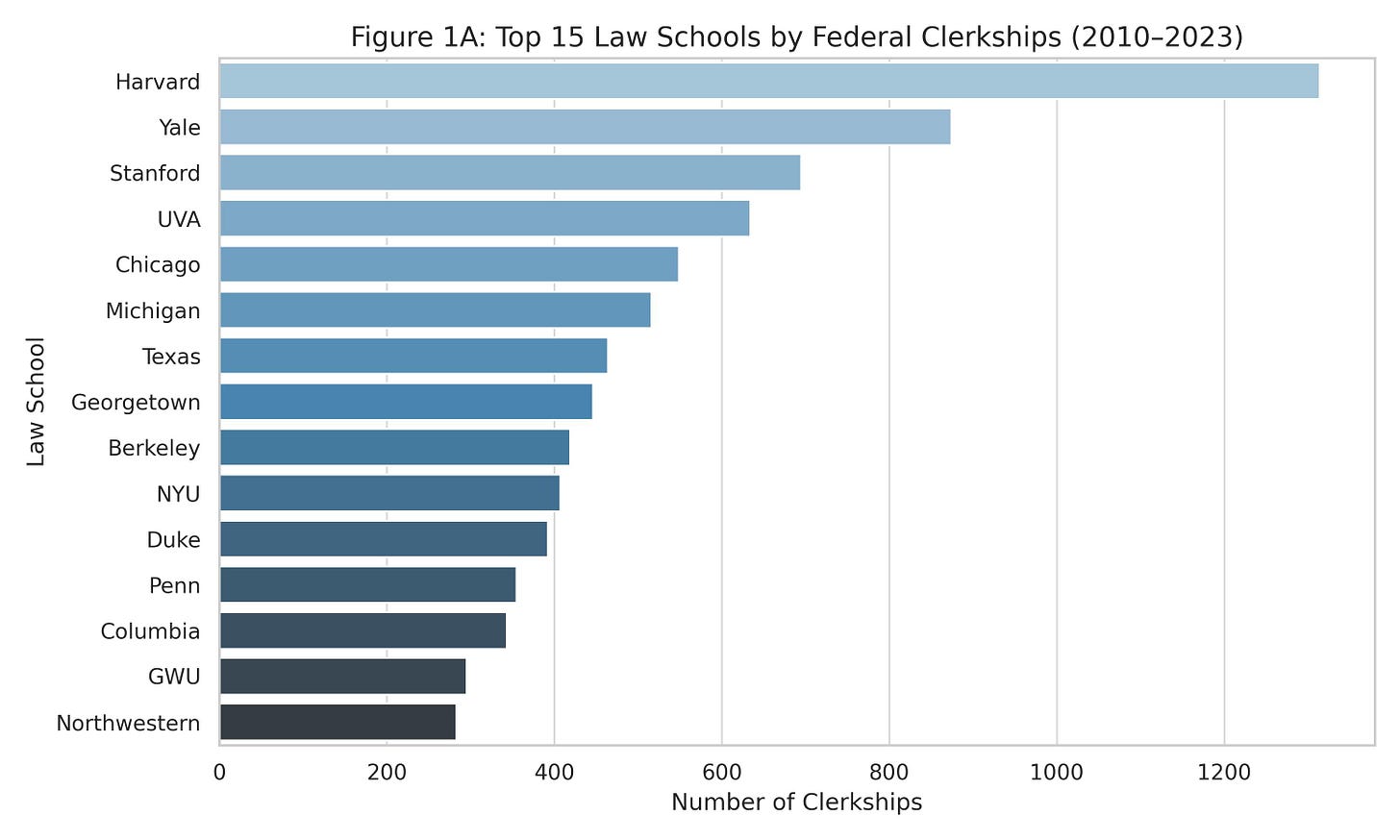

This trend, or capture, of the Supreme Court by a select number of schools extends down into every level of the federal judiciary—an outsized share of federal judges hail from a small cluster of top-ranked institutions—especially Yale Law School, Harvard Law School, and, to a slightly lesser extent, Stanford Law School. Nearly half of all federal judges in U.S. history graduated from one of just 20 top law schools. Likewise, the feeder role of these schools in clerkships, the coveted postgraduate positions with judges that often precede a judicial career, is pronounced. 46% of all federal law clerks come from one of 15 elite law schools.

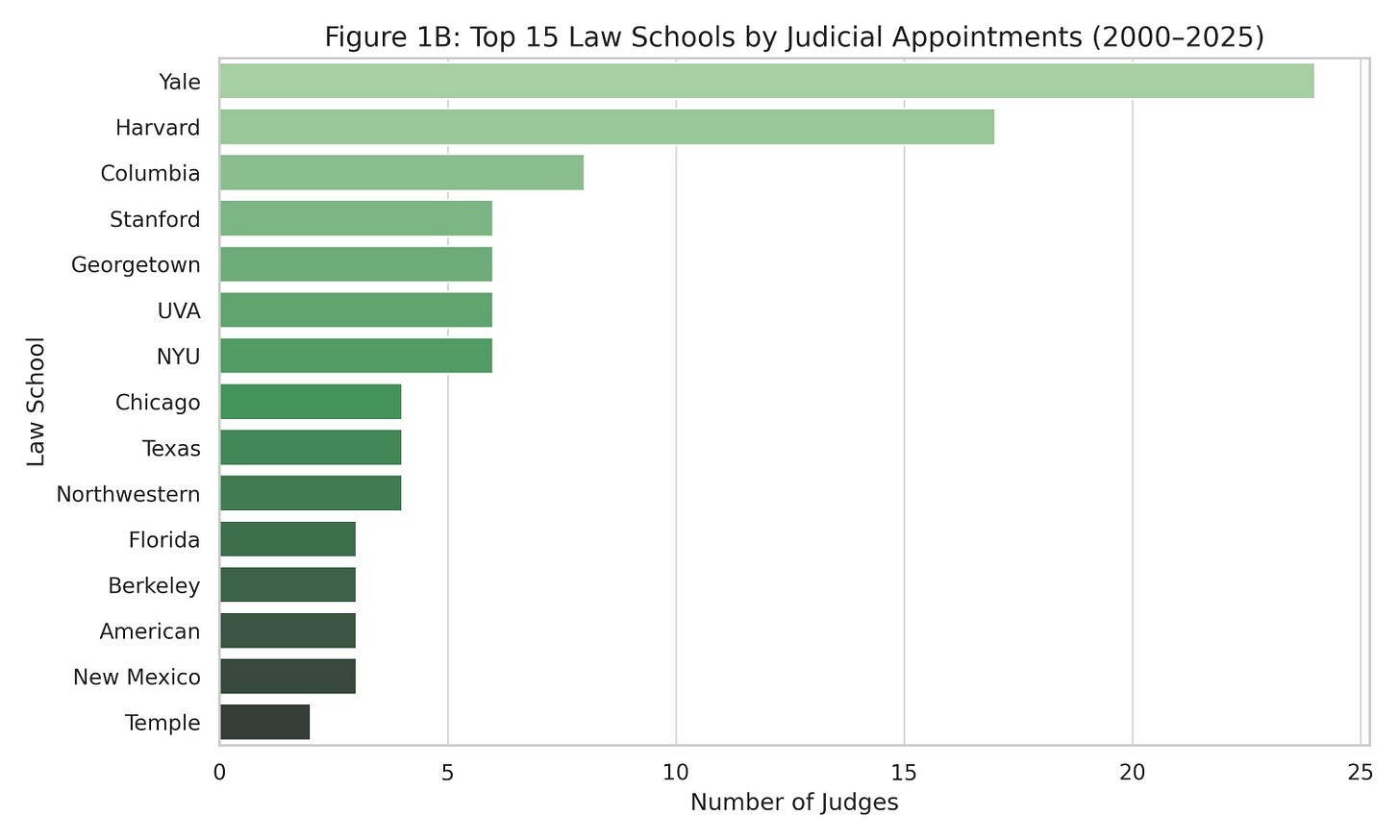

From 2000 to 2025, Yale, Harvard, and Columbia accounted for 30% of all federal judicial appointments.

There are 197 accredited law schools in the United States. To drive this point home, 1.5% of law schools account for 30% of federal judicial appointments. Expanding to the traditional “T14” elite schools captures well over half. Conversely, the long tail of law schools contributes very few judges: approximately 80% of the 68 law schools with a judicial appointee produced only one or two judges. This data gives the impression that the federal judiciary’s talent pool is broad (hundreds of judges from dozens of law schools), but in reality, it is fed by a very narrow channel of schools.

It's not just the justices that are concentrated among a few schools, but their clerks as well.

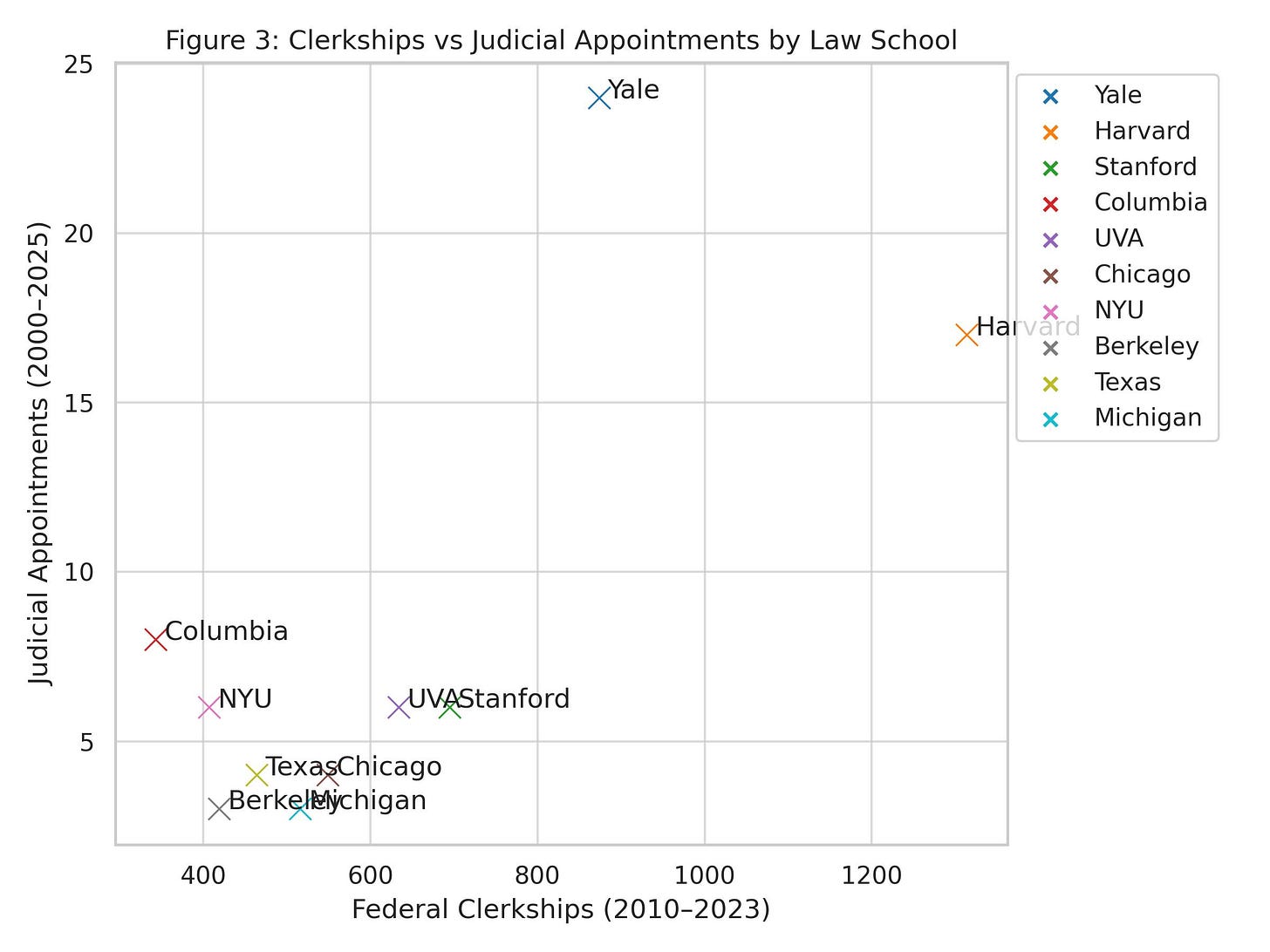

There is a strong correlation between a law school’s success in placing graduates in federal clerkships and its success in producing federal judges. Schools like Yale, Harvard, Stanford, and UVA top the clerkship charts and rank highly in judicial appointments. The statistical correlation between clerkship placements and judgeships by school is visible in a scatterplot of the two variables.

The points reveal a roughly linear trend: More clerkships = More Judges. Yale Law is an outlier, having more judges than one would predict solely from its (already high) clerkship count, suggesting Yale’s clerk-to-judge “conversion rate” is particularly efficient. Harvard Law, by contrast, has an enormous clerkship output but slightly fewer judges than Yale. Still, Harvard’s sheer numbers are near the top in both categories. Other elite schools cluster together (Stanford, Virginia, Columbia, NYU, each with hundreds of clerks and a handful of judges). Meanwhile, schools with low clerkship numbers generally have correspondingly few (if any) judges.

A few interesting exceptions emerge: for instance, the University of New Mexico and American University produced 2–3 judges each despite relatively modest clerkship counts. This suggests alternative, idiosyncratic routes to the bench, perhaps due to regional advantages. There are also more public school representatives at the top of the clerkship list than in the federal judiciary data, indicating something happens to these public school students in the pipeline, either from their own choosing or in the appointment selection process. This would be interesting data to overlay with Congress, particularly the Senate Judiciary Committee’s educational backgrounds. All in all, however, the general rule remains: a strong feeder school pipeline for clerkships translates into future judicial representation.

From these patterns, one can discern the feedback loop at work: Elite schools secure the most clerkships; those clerk alums gain experience, credentials, and connections that later make them attractive judicial nominees; once on the bench, judges often hire new clerks from their alma maters or similarly elite schools, thereby perpetuating the cycle. Our findings mirror those reported by external observers. For example, a recent Harvard Law Review study of appellate judges found that judges who attended top-20 law schools are significantly more likely to hire clerks from top-20 schools. In contrast, judges from non-elite schools often hire more (but not a majority) of clerks from non-elite schools.

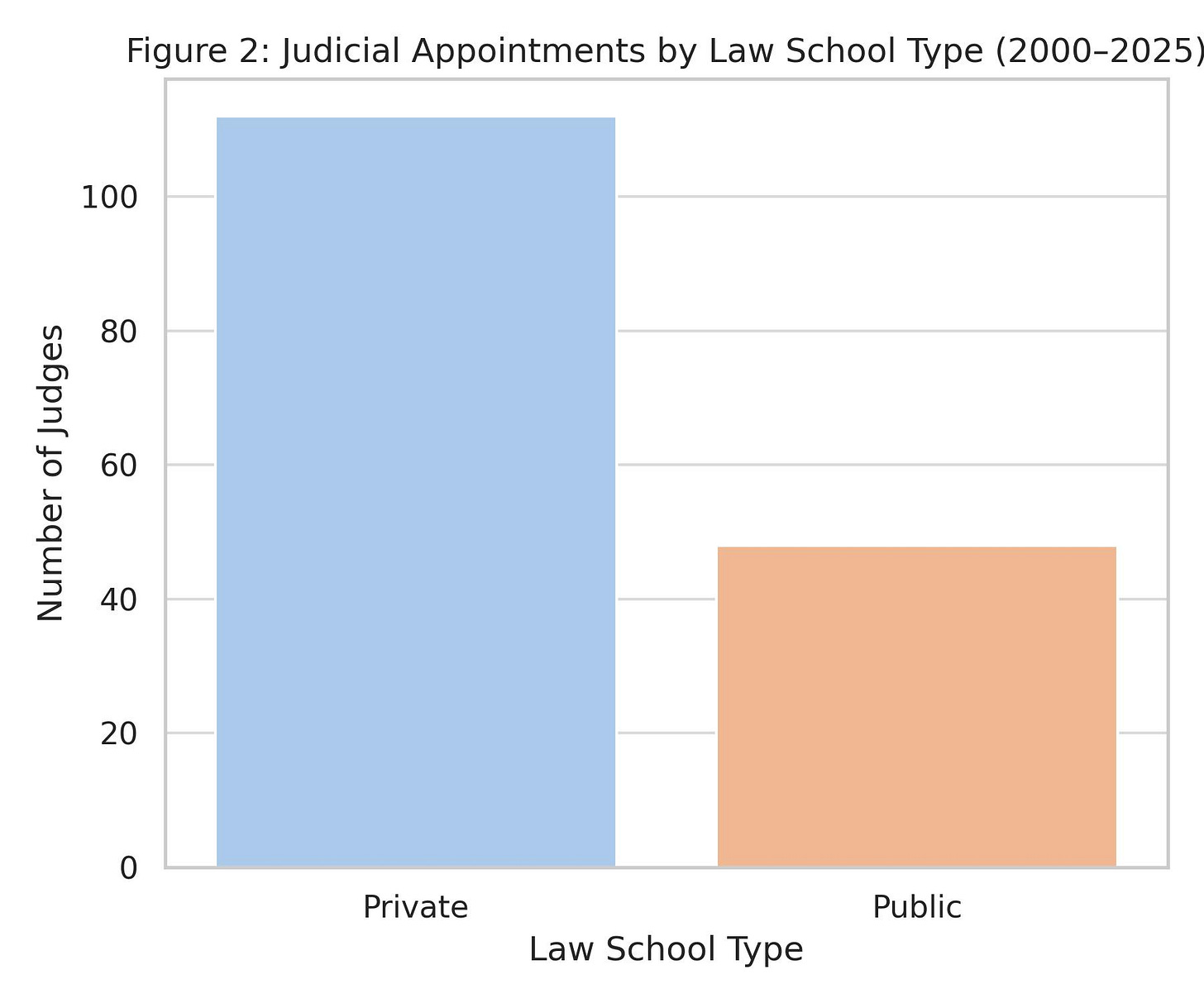

One striking aspect of the pipeline is the dominance of private law schools over public ones. Most elite institutions funneling graduates into clerkships and judgeships are private. Even highly ranked public law schools like the University of Virginia, University of Michigan, UC Berkeley, and University of Texas appear less frequently and typically with lower numbers.

Around 70% of federal judges appointed 2000–2025 received their J.D. from a private law school, versus ~30% from public law schools. Likewise, roughly two-thirds of all federal law clerks (2010–2023) graduated from private institutions.

This imbalance correlates closely with law school rankings: of the traditional “Top 14” or “T-14”, only three are public (Virginia, Michigan, Berkeley), and those three are the only public schools consistently appearing among top feeder schools for the federal courts. The prestige hierarchy of legal education, which historically favored Northeastern private universities, is replicated in the composition of the judiciary. Public law schools, even excellent ones producing many capable graduates and serving diverse regions, are underrepresented on the federal bench.

Held at the gate

For many aspiring judges, a federal judicial clerkship is an essential early career step. Clerkships, typically one- or two-year positions assisting a judge with research, drafting opinions, and case management, provide new lawyers with an insider’s view of the courts, forging close relationships with judges and valuable mentorship. Importantly, a prestigious clerkship (especially at the Supreme Court or appellate level) has become a de facto credential for those on a judicial career track.

It is little surprise that the competition for clerkships is fierce, and judges are highly selective in choosing clerks. Many judges (consciously or not) use elite law school attendance as a proxy for quality when hiring clerks. This is yet another feedback loop: without the prestigious alma mater, it’s much harder to land a clerkship that could demonstrate their abilities, yet without clerkship experience, it’s harder to later be seen as a top candidate for higher positions.

Justice Antonin Scalia articulated judges’ preference for elite law students:

“By and large, I’m going to be picking from the law schools that basically are the hardest to get into. They admit the best and the brightest, and they may not teach very well, but you can’t make a sow’s ear out of a silk purse.”[sic]

In practice, this means that a 2-page admissions essay and an LSAT score are enough to filter out most law students from ever being considered for a clerkship, much less the federal bench. This is not to say that the pathways to clerkship and the judiciary are not based on merit, and I’m not suggesting that Scalia is wrong in saying that the T-14 does not attract some of the best and brightest. It’s just that the meritocracy is only reserved for a few, and the rest are effectively denied an opportunity to participate in an entire branch of the federal government.

Retaking the park

So why does this matter? For this data to elicit any type of frustration, you have to accept that 1) law students who get into Harvard or Yale are not somehow predisposed to being superior lawyers and 2) public law schools produce equally capable and intelligent legal scholars.

Even if you are still captivated by the crimson brand of Harvard, it should still trouble you that an entire branch of government has essentially privatized and outsourced its selection process to basically two schools. In Congress and the Presidency, candidates must sell themselves to the people, serving as the ultimate check. Consequently, there is far more diversity in educational background.

The two studies I cited frequently in the post propose two possible solutions. One study published in the Columbia Law Review, “Some are more equal than others: U.S. Supreme Court Clerkships,” proposes to bring transparency to the clerk hiring process. Clerking is a government job, they say, so it is baffling that this position is not subject to the same transparency and scrutiny as other positions.

The second, a piece published by the Center for American Progress, “Building a More Inclusive Federal Judiciary,” recommended a version of the “Rooney Rule” for Clerkships. Quoting Judge Vince Chhabria of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, who suggests:

that judges adopt a practice similar to the NFL’s Rooney Rule, whereby judges would be required to interview at least one candidate from a demographically underrepresented group and at least one candidate from a law school not ranked in the top 14 for clerkship positions. According to Judge Chhabria:

“Obviously, I don’t always hire law clerk candidates who meet this description. But interviewing off-the-radar candidates has sometimes led me to hire a fantastic person who might not originally have been given an interview. Other times I’ve not hired the person, but the interview with me has led to interviews with other judges (often on my recommendation). Overall, my hiring process has been better because of this practice, and it has resulted in stronger chambers.”

I propose solutions rooted in the current structure of the court system. The federal judiciary is divided into districts at the lowest level and appellate circuits at the next level, before getting to the Supreme Court. This system is divided geographically, with its roots from when judges had to “ride the circuit” on horseback and hear cases around the country. Because of the geographical divisions, different circuits take on different types of cases and subsequently judicial philosophies.

District and appellate courts should be required to hire a certain percentage (probably at least 50%) from schools within the circuit.

This may not address the public-private law school gap, but it would, at minimum, diversify the clerkships, allowing more law students and graduates an opportunity to compete and acquire the network crucial to obtaining a judgeship. As an aside, I also think that the Supreme Court should mirror the circuit courts: One judge on the Supreme Court pulled from the geographic region of one circuit.

Regardless of the solution, the most elite club of lawyers in the country does not have to stem from the most private club of law students. For the republic to function and prosper, our institutions must grow from the public.

Academia & methodology note: This post examines how and why graduates of elite private law schools dominate the federal judicial pipeline, and what consequences this “pedigree bias” has for the judiciary and the public. We leverage two unique datasets covering federal judicial appointments (2000–2025) and federal clerkship placements (2010–2023) by law school, alongside prior research and reports, to quantify the extent of elite law school concentration. The federal judicial appointments were pulled from the Federal Judicial Center in March 2025, and the clerkship data were pulled from the American Bar Association in April 2025.