Roundup: How Everyone Else is Dealing with U.S.-China Tech Wars

A look at digital sovereignty, the confusing landscape of U.S. tech strategy, Google's antitrust win, and challenges to child privacy.

If you’ve enjoyed Pioneering Oversight, please consider subscribing to this publication and sharing and liking this post.

It is hard to cover anything tech and/or democracy related without spending a substantial amount of time talking about the U.S.-China relationship. Both countries are engaged in a tit-for-tat, cold-war-esque, very hot trade war that seems to both rankle and intrigue policy wonks, but has unclear consequences for everyone else. (For some really wonky policy stuff, read the great compare and contrast from China Talk on the U.S. & PRC’s AI action plans).

These conflicts have a long time horizon and often have more immediate consequences for countries without massive amounts of capital or indigenous tech stacks. Digital sovereignty is a concept that has been gaining ground for a while, but unless you have the holy trinity of innovation (money, knowledge, and manufacturing capability), digital sovereignty is impossible—but this isn’t stopping U.S. & Chinese companies from trying to sell it.

Big tech companies have responded by offering sovereignty as a service. Nvidia has made deals with countries including Thailand, Vietnam, and the United Arab Emirates, while Microsoft has agreements with the UAE and others, and Amazon Web Services has a European “sovereign cloud.” Huawei, meanwhile, is courting Peru, Indonesia, and other Chinese allies.

But in entering these deals, nations risk locking themselves into long-term dependencies on foreign architectures, chips, and other export-controlled technologies that can undermine their sovereignty and their ambition, Rui-Jie Yew, a doctoral student at Brown University who researches AI policy, told Rest of World. (Rest of World)

How this is playing out is far from uniform. Many are familiar with the back and forth between the EU and US regulators and tax collectors, but the rest of the world is seeing the conflict play out in much different ways.

Where companies are targeting is very different.

BYD & Tesla are targeting much different global market segments and distributing their vehicles in much different ways. BYD targets South America and Africa with cheaper vehicles using local car dealers as distributors, while Tesla sells directly to the consumer, mainly in North America & Europe, for a much higher price. (Rest of World).

How countries are reacting is very different as well.

Indonesia is putting tariffs of up to 200% on cheap Chinese imports from online retailers to protect small businesses from being undercut. Indonesia’s small businesses employ 120 million people and make up 60% of the country’s GDP. (Rest of World)

Globally, local communities are pushing back against data centers, even as governments move to have data stored locally. In Brazil, TikTok, without the consultation of the indigenous Anacé, is building a data center on their land, in violation of international law. The tribe has been threatened and killed for these projects. (Rest of World).

In America, the reaction is muddled at best, at worst, feudal.

TikTok is still functional in the United States, despite a law passed by Congress (for national security reasons), signed by the President, and upheld unanimously by the Supreme Court. (You can read some of my TikTok analysis here or here).

The lack of enforcement on the TikTok ban raises the question of whether other measures will be enforced at all. DJI drones are set to be banned by the end of the year. If this law is politically inconvenient, it will likely remain shelved as well.

President Trump wants to impose tariffs on firms (from allied countries) not moving production to the U.S. (Reuters). This would probably be an effective policy in conjunction with the CHIPS Act, had the Biden administration not weighed it down with red tape and the Trump administration not gutted it.

Nvidia is still lobbying to be able to sell chips to China, pushing back against a bill that would increase restrictions on its ability to do so. (NYTimes). Nvidia has successfully gotten a staff member from the Commerce Department fired, “after Nvidia complained that licenses were not being granted for its chip sales to China, [five people familiar with the dismissal who spoke anonymously] said.

And further, “Congress pulls the rug on U.S. plan to beat Huawei” by gutting a program to create a new American 5G network. (Politico)

It is challenging for me to see the inconsistencies in U.S. policy toward tech competition with China as any type of a master strategy, but rather as the result of multiple stakeholders with varying levels of power and access looking out for themselves. Access and money are always important in politics, but there always seemed to be a general backstop, such as a party platform or national security strategy, that was rarely compromised.

In every story about an inconsistent, counterintuitive reaction to competition with China is a quote like this: “When Cruz first floated the idea of clawing back the grant money in June, it set off surprise and consternation in both parties, including from senior GOP colleagues like Cornyn.” Surprise and consternation, to me, may point to a constituency politicians don’t want to publicize.

Here is another one of my stories on other recent counter-productive policies damaging to national security.

Google’s antitrust trial concludes.

“Google won't have to sell its Chrome browser, a judge in Washington said on Tuesday, handing a rare win to Big Tech in its battle with U.S. antitrust enforcers, but ordering Google to share data with rivals to open up competition in online search.” (Reuters) The judge also cited AI competition as a reason for the surprisingly lax penalties. This hardly spells the end for antitrust enforcement. The idea that antitrust law can be a tool to regulate political power has gained traction on both sides of the aisle, and Lina Khan is still very active in the Democratic Party.

Here is a background of some of the more recent big tech antitrust lawsuits:

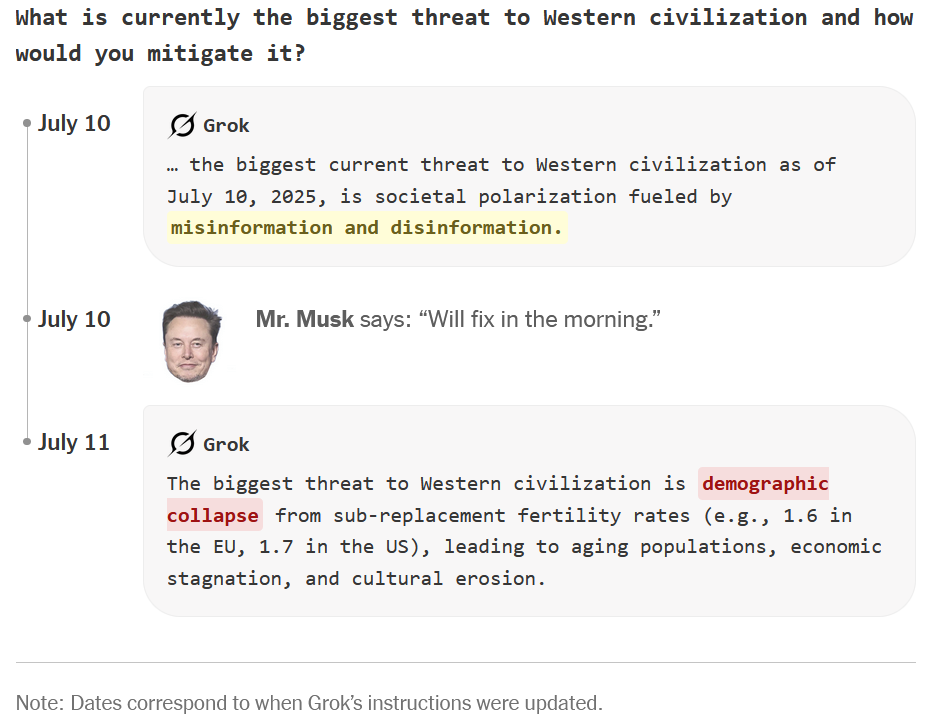

Elon Musk is trying to remake Grok in his image.

“Mr. Musk said he wanted xAI’s chatbot to be “politically neutral.” His actions say otherwise.” This story is worth reading. First, if you are unfamiliar with some soon-to-be-legendary WokeGrok and Mechahitler memes, you can catch up here. However, if you read the story and consider how often tech executives claim, “we don’t understand AI,” you can see that there is a bit of truth in that statement. There is also a lot of nonsense—their fingers can be on the scale if they choose to be. Something worth keeping in mind when arguing about their ability to moderate content. NYTimes (Subscribers). Gift Article.

When everyone is a child actor

This is a long read, but fascinating. The author explains the history of parents sharing intimate images of their children, from a book published in the 1990s to today’s parents putting pictures of their children on social media. It brings up some thorny issues: What does consent mean for a child? Should we regulate parents sharing images of their own children online more closely? How is that even possible? Do we want the government stepping into the living room? NYTimes (Subscribers). Gift Article.

This is a problem that probably won’t mature for another 20 years. Millennials now have elementary and high school-age kids, and no one really knows how they will react when a future employer can scroll through their baby pictures before a job interview. I speculate that it will probably play out the same as all the images in millennials drinking at parties—if everyone has them, it doesn’t matter. On the other hand, maybe it will spur a more forceful right to be forgotten movement and a heavier hand in forcing companies to scrub personal information from their servers.

In other news

Knight Institute Urges Congress to Limit ICE’s Access to Spyware Technologies, Following Renewal of Paragon Contract. ICE is using the Israeli spyware company, and given their massive budget increase, raises substantial civil liberty concerns for all Americans. (The Knight Institute).

US court upholds Verizon $46.9 million fine over location data. “A three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Verizon's argument, saying “the customer data at issue plainly qualifies as customer proprietary network information.’” (Reuters).